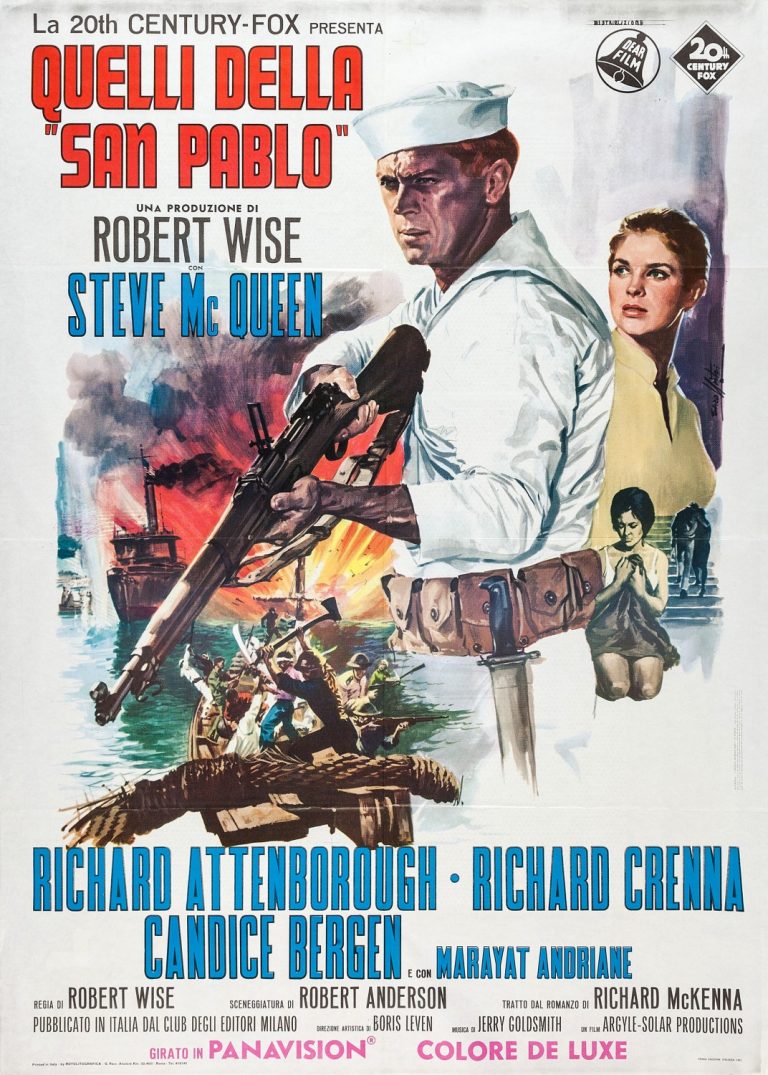

1966, d. by Robert Wise. With Steve McQueen, Richard Attenborough, Candice Bergen, Richard Crenna, Gavin McLeod (who always looks at home in a sailor’s suit) and James Hong, who would one day play the host of the Chinese restaurant in the second episode of Seinfeld. You know the guy I’m talking about…

I’ve been on a Steve McQueen kick lately. He didn’t make that many movies, so I was surprised to learn of one that I had never heard of, but was quite a big deal in its time.

Fresh off his 1965 Oscar win for Best Picture with The Sound of Music, director Robert Wise turned to 1920s China for his next epic adventure film. Between The Sound of Music & West Side Story (1961, also Best Picture winner), it is easy to think of Wise as a director of musicals, but his long career was mostly about action and sci-fi, including The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), Run Silent, Run Deep (1958), and Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). The Sand Pebbles was an easy fit for him, and one can imagine him happy to shake loose the Musical Director label.

While it is not smart to learn history from film, it is always a pleasure to learn of history from film. Why did we have American gunboats up the Yangtse River in the 1920s?! The simple, if flippant, answer is Calvin Coolidge’s statement that “the business of America is business.” We were protecting nascent commercial interests in a foreign land, a land of warring tribes and warlords wary and growing restive over the presence of foreigners imposing their will and taking their resources. It’s the same old story.

The film’s release coincided with our uneasy escalation in Vietnam. The movie-going audience of 1966 would have noticed the parallel ambiguities of our heavy footprint in southeast Asia; more on that later. The story takes on dimension now, from today’s context, in which the dynamic as portrayed is rapidly inverting: China the ascendant heavy footprint, America the fractious tribes in confused retreat.

When our man Jake Holman (Steve McQueen) arrives for his new commission as chief engineer of the gunboat San Pablo (nicknamed The Sand Pebble by its crew), he is met by a native coolie who wants to carry his luggage. Jake demurs, he can handle it himself, but is quickly told by a fellow sailor that to deny the chance for the Chinaman to earn a tip is to “take rice out of his bowl.” We are tipped off that the relationships among people, cultures, ranks, and vocations is not as clear as would seem. Just who is in charge of whom, and how? That is only the beginning, as we learn with Jake the extent to which Chinese nationals work aboard the ship– not as manservants but as the actual sailors, in clear subversion of US military protocol. They are under the ruthless direction of their Chinese boss, through whom all shipboard orders– US naval orders!– must be passed and processed. The simmering tensions which all are determined to ignore is but one of several powder kegs to which we are introduced in the first act of the film.

We warily go ashore with the sailors on leave. In the port town we meet characters savory and unsavory, equally representing all of the cultures involved. Among the worst are the sweaty American businessmen whose interests we are risking life and limb to protect while they enjoy the fruits of un-civilization in a way they dare not at home. Even worse, potentiallly, are the nascent Chinese communists, bent on uniting the various Chinese cultures with “their new weapons: propaganda and nationalism,” as one observer notes.

It is back on the boat that I see the most fascinating aspect of the scenario. It is not about a comparison between 1920s sensibilities and today’s, but between the 1960s sensibilities at the time of the film’s making, and today’s. To wit: the adoration, if not outright fetishization of Holman’s gunboats’ engine. An engine! A piece of machinery, in this balancing act of humanity. The camera pans and lingers over its gleaming pistons. No narrator, no expository dialogue explaining to the audience what we are looking at or how an engine works; it is assumed that we, middlebrow middle American consumers of the new Ford Mustang already know. And appreciate. And are proud.

This is what makes us great. This is what will save us, and them. This concept called engineering, where we harness the powers of the universe with such precision, and with such good intentions, that superstition and rivalries don’t stand a chance.

This is underscored in a great scene a bit later, where Jake bucks all authority– Chinese and naval and social– to take one of the laborers under his wing and explain to him through the language barrier exactly how the engine works — with gestures and pidgin Chinglish. We figured this out, we Westerners. We are sharing it with the world. We are the saviors.

Pride goeth before a fall. Both in the movie and as I say, looking at the movie from today’s world.

The plot is thick, with several threads intertwined of various characters. The geopolitics are explained and then unwound, as they will. Caught up in the maelstrom are a fetching, young Candace Bergen, as well as Richard Attenborough with a mostly convincing American accent. (In some ways more convincing than McQueen’s, whose character is supposed to hail from Utah but sounds oddly like he’s from Brooklyn). Possibly most interesting of all is Richard Crenna as the beleaguered captain; I have a feeling that in the novel upon which the movie is based, his is probably one of the more interesting characters. He seems a typical politicized flag officer at first, but towards the end we are allowed to understand and sympathize with his motivation as he maintains a constant balance among hostile forces from below, above, and all around.

And about that ending: what an ending we are given. At some point the geopolitical tensions are cut loose from their moorings and we are given a naval battle and rescue mission as fine as any war movie of the era. American heroism and honor are on full display, even as the cause grows increasingly lost. Is there anything more satisfying, really, in a war movie, than the officer who bucks the bureaucracy for the sake of his men and/or civilians?

How had I never heard of this movie before? It was well-received when it was released, and McQueen was at the peak of his career, just before Bullitt (there’s that Mustang again…) and The Getaway. Expertly filmed by a recently and deservedly acclaimed director.

I suspect the culprit was Vietnam. Who wanted to go to a movie theater in 1966 to watch an American military presence in Asia of dubious morality and competence? Plus, the material was just a touch complicated for sustained interest; sympathetic Asian characters and rapacious American and British characters muddied the simplistic narrative of McNamara, Cronkite et al. I’m guessing the film probably got zero play on late night or Saturday matinee movie shows in the 60s and 70s, which is where so much of my (generation’s) film education was born.

As pure entertainment, it is first rate: visually stunning, in an interesting setting, with complicated characters acted by some of the finest performers of the day. It deserves to be remembered, and I daresay some of its sobering lessons about intercultural affairs, human nature, and political entanglements should be seriously contemplated.